Lessons From Managing My First Race

How we swung a district 53 points from Trump’s 2016 margin—and what it taught me.

We were never supposed to win. Or for that matter, come anywhere close. After my first cycle as an organizer in 2016, I went back to college at a small liberal arts school—Truman State University. One fall day, on the way to class, a call came in from Jim Scaggs—a County Commissioner who was planning to run in a special election for Missouri House District 144.

A year and a half earlier, Jim and I had met when I became a national delegate for Bernie Sanders. Jim chaired the congressional committee that selected delegates, and he knew I’d worked on a campaign in 2016. He asked if I knew anyone who could help with his race. I thought of my friend Carter Gibson—who had also worked as an organizer with me that cycle—and told Jim I might have someone in mind.

The next day, I called Carter and told him about the race. Neither of us had ever managed a campaign. We were both full-time students—Carter was 1.5 hours from Jim, and I was about 4.5 hours away. But after a few days of talking it over, we decided to do it together. First, we had to convince Jim.

We set up an in-person meeting on a Wednesday night. Even though we didn’t know much about managing, we had friends who did. With their help, we scraped together a rough budget, a basic fundraising plan, and a simple field strategy. We pitched it all to Jim, and he signed on. We were officially campaign managers.

The race

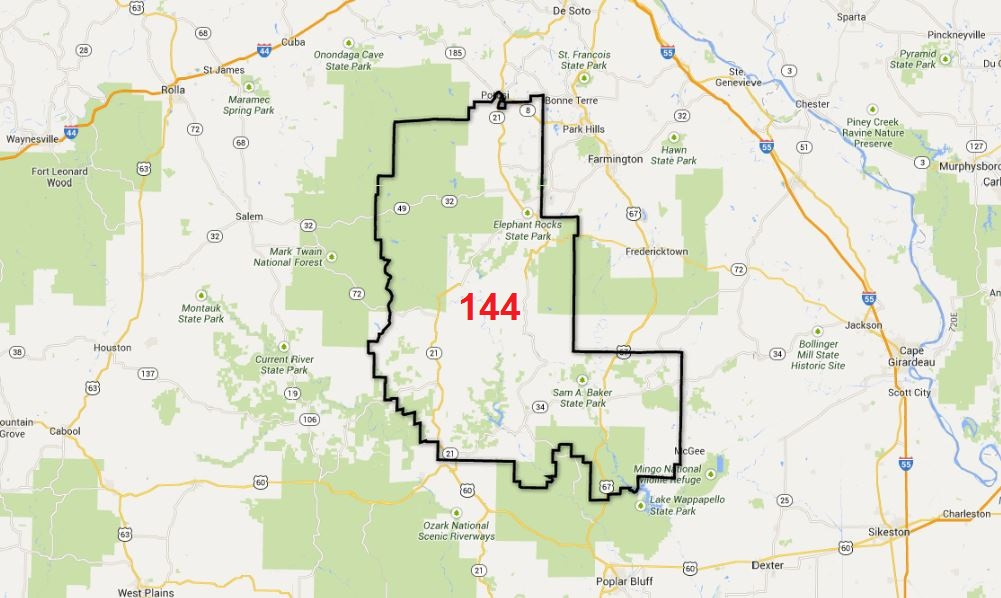

Nestled in southeast Missouri, HD-144 is a rural district that stretches across the Mark Twain National Forest and several state parks. It includes all of Iron County, most of Reynolds County, parts of Wayne County, and a sliver of Washington County. The largest town is Potosi, with just 2,538 people.

Just how red was the district? Looking at precinct results from 2016, Trump got 78.34% and Clinton got 18.70%. Nobody saw it as competitive.

At the same time, three other special elections for Missouri House seats were underway. Most of the attention was on HD-97, a suburban district just south of St. Louis. But two of the four counties in HD-144—Iron and Washington—had gone for Obama in 2008. This was classic “Obama-Trump” working-class territory, with deep union roots.

Our strategy was straightforward: go all-in on field, leverage our network of friends and students, and most of the budget on mail and paid communications. We set a budget of just over $40,000—a stretch, but enough to get real messages out to our universe of 5,569 voters.

Lesson 1: Localizing issues are important

We stuck to bread-and-butter issues—healthcare, education, jobs—but we didn’t just repeat national talking points. We made those issues local.

Take Medicaid expansion, for example. Missouri had the chance to expand Medicaid, but the legislature refused. Instead of quoting stats, we told a local story: In the southern part of the district, Southeast Missouri Health Center had closed. That left many residents more than an hour from the nearest hospital. Within a year of that closure, a police officer in his 40s died of a heart attack. He lived just 10 minutes from the hospital that had shut down.

That story hit home. It made the policy real.

On education, we focused on rural school districts that had been forced into 4-day school weeks because of Republican budget cuts. Jim’s experience on the local school board helped us highlight how critical it was to fully fund rural schools—not just for students, but for communities.

Lesson 2: Candidate Quality Is Important—But Money Is Vital

Jim was exactly the kind of candidate you hope to have in a competitive race. He had deep roots in the community—he was the sitting Iron County Commissioner, had served on the local school board, and owned a small business. When we talked to voters, people didn’t ask who he was—they already knew. That kind of local credibility is invaluable, and it’s part of why the race ended up being so close.

But in the end, it wasn’t enough.

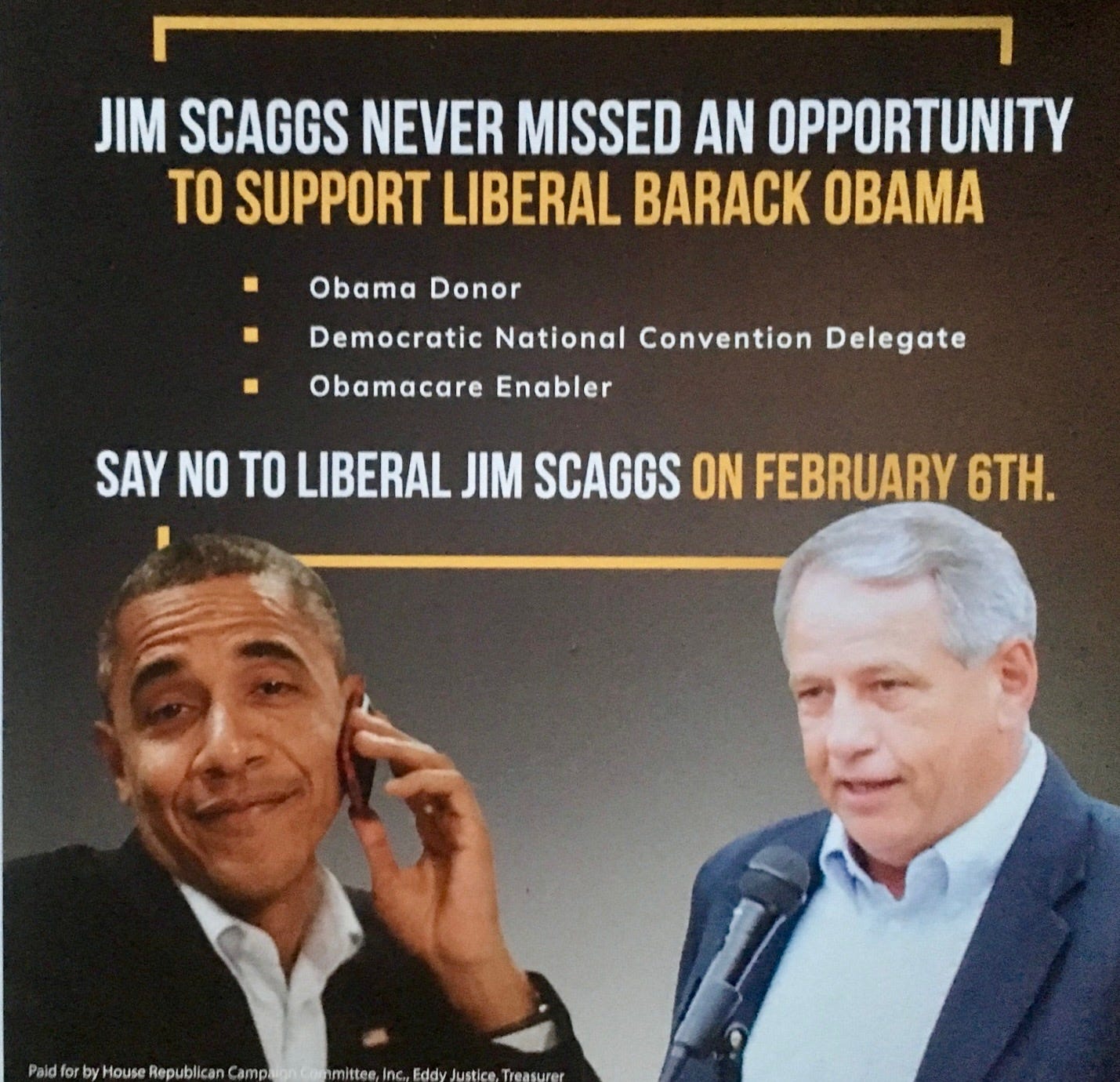

We raised and spent just over $68,000—no small feat for a special election in a deep red district. But our opponents, when you include outside spending, poured in over $250,000. That kind of spending disparity is hard to overcome, no matter how good your candidate is. They were in every mailbox. And toward the end, they had enough money to go negative and define the race on their terms. While our opponent relied heavily on outside help, our campaign never got a dollar from an outside group to help us.

We had a great candidate. We had a strong message. But we didn’t have enough resources to match their volume—or to fight back when they went on the attack. That was a hard but necessary lesson: In campaigns, quality matters—but money moves the message.

Lesson 3: Organizing Makes a Difference

We didn’t have money to burn, but we had people—and we put them to work.

Our field program was built almost entirely on the backs of interns and volunteers, many of whom we had met through previous campaigns. These were students, young organizers, and friends who believed in the work and gave their time freely. Because the district only had about 1,000 knockable doors—spread out across a vast, rural area—we focused heavily on phones.

In just two months, our team made over 52,000 phone calls to a universe of about 5,500 targeted voters. And we still hit the dirt road—we knocked those 1,000 doors twice. Every conversation we had helped us refine our universe, our message, and our strategy.

And the results showed—not just in how close the race ended up, but in voter turnout. HD-144 had 5,708 votes cast and we lost by just 300 votes.

For comparison, there were three other special elections happening at the same time:

HD-129: 3,117 votes cast

HD-39: 3,026 votes cast

HD-97 (the only other competitive race): 3,467 votes cast

We had the highest turnout of any special election in the state that day—by a mile. That wasn’t an accident. That was organizing. When you show up, talk to voters, and build real relationships, it makes a difference. Even in the reddest corners of the map.

Bonus Lesson: Going negative is necessary

Our opponent, Chris Dinkins, didn’t hold back. Her campaign and outside groups unloaded—more than eight negative mailers, radio ads, robocalls—the full playbook. They defined the race early and aggressively, painting a distorted picture of Jim and our campaign. It was loud, constant, and impossible to ignore.

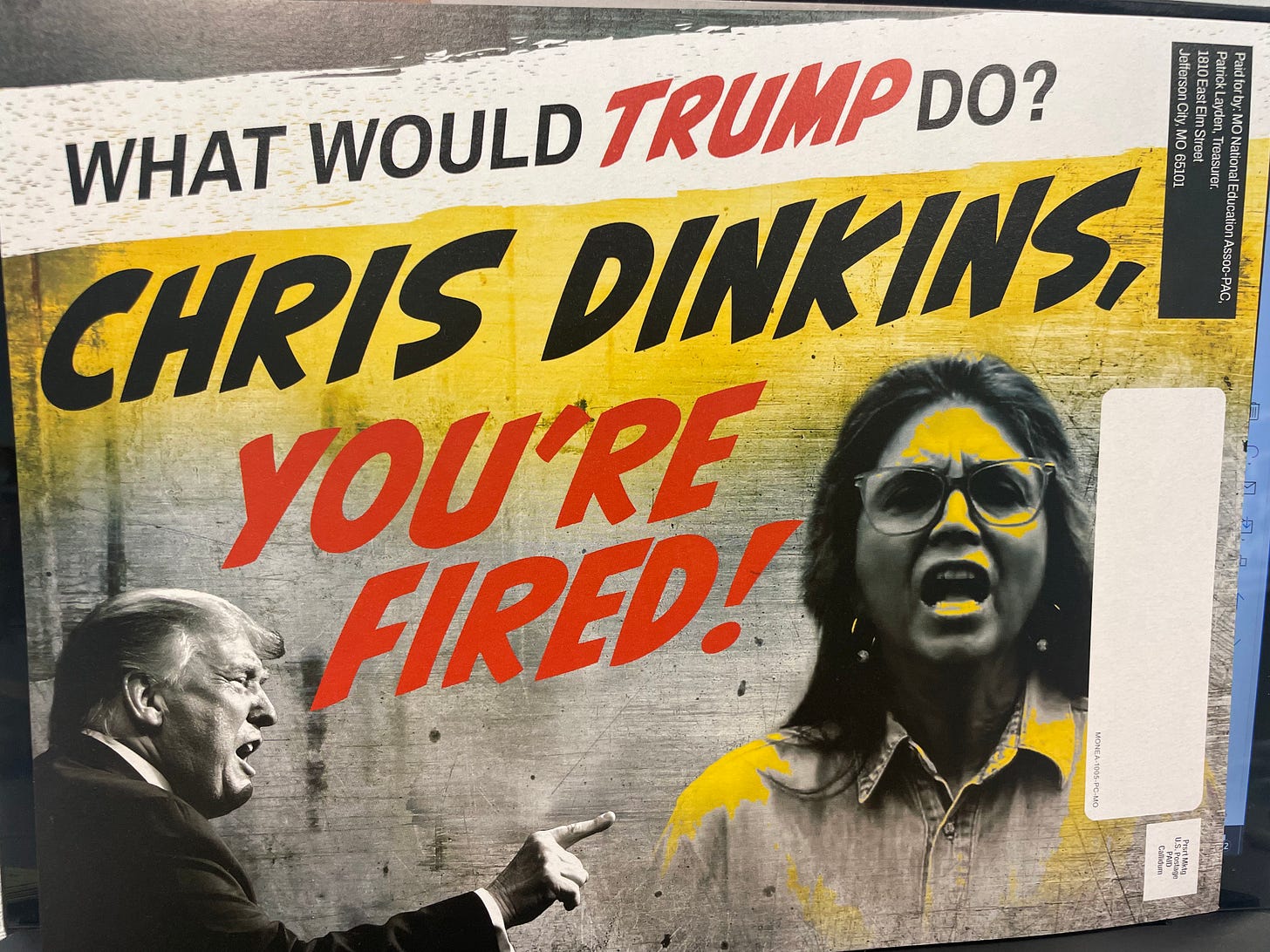

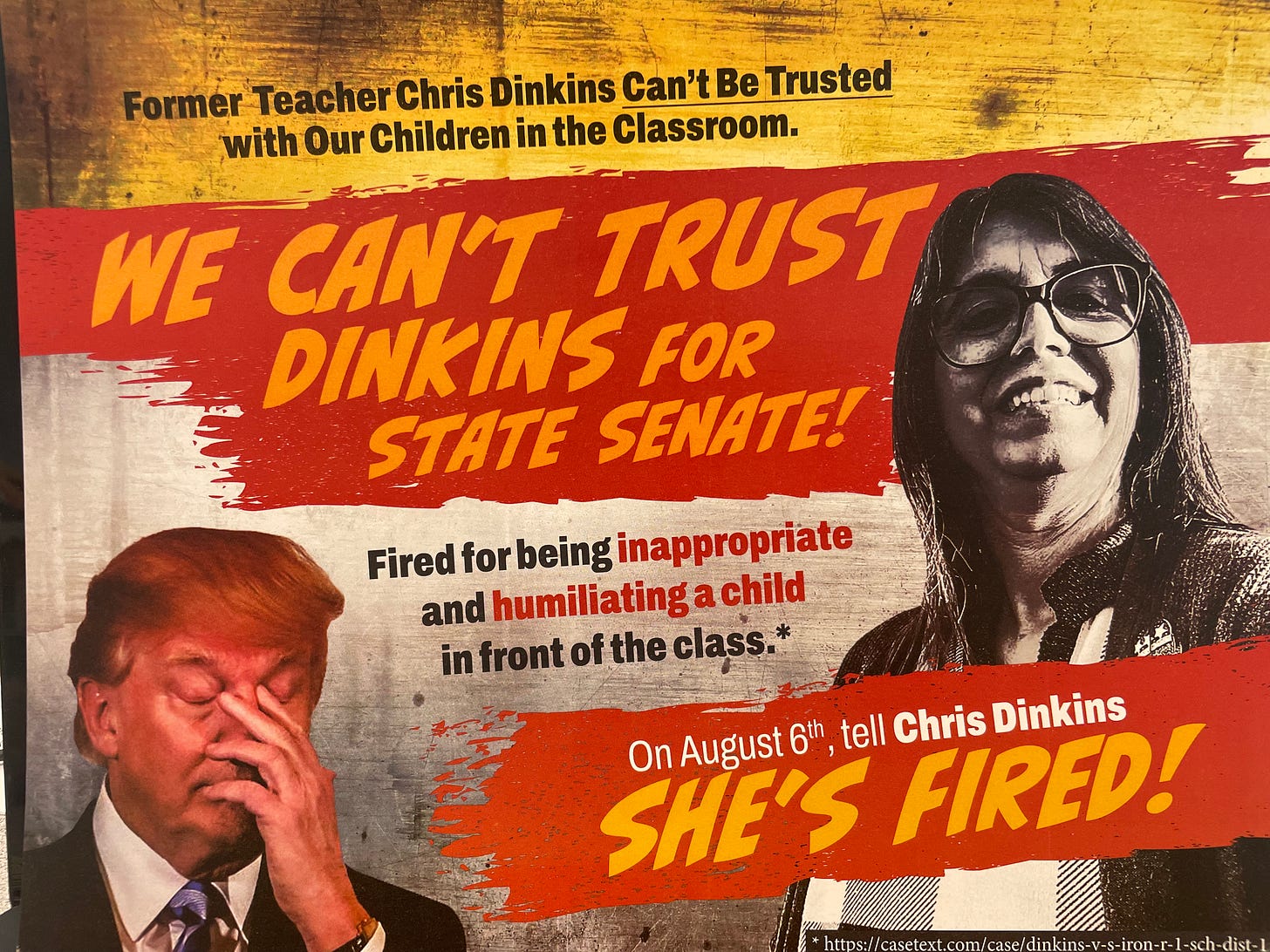

We had a story to tell, too. We knew Dinkins had been fired as a teacher, and parts of it were public record. The contrast was clear, and I had the mailer envisioned—in the era of Trump what better headline than “You’re Fired”. It would’ve landed.

But, we didn’t send it. Without the budget to push it out and without consensus to go negative, we stuck to our message and left that story untold. It was a missed opportunity.

Years later, when Dinkins ran for State Senate, that exact piece finally showed up in mailboxes. The same contrast, the same story—and she got crushed, finishing third in the primary by 18 points.

To this day, I believe we could have won that House seat. We had a strong candidate, a sharp message, and serious momentum. But we didn’t draw the contrast voters needed to see. Going negative isn’t about being nasty—it’s about being real. If you don’t define your opponent, they will define you. And in close races, that can make all the difference.

A Race Worth Running

About a month before Election Day, I got a call that changed everything. An external poll had come back—and we were statistically tied. Just a few points behind Dinkins. After months of pouring everything we had into the campaign, it was the first sign that maybe—just maybe—we could pull this off.

That poll didn’t just energize us—it shifted strategy across the state. The Republican House Committee had one final chunk of money to spend, about $20,000, and they were deciding between our race in HD-144 and another in HD-97. They chose ours. They had polled both and believed we were the bigger threat.

HD-97 flipped on Election Night. A Democrat won. We didn’t. But by building something competitive where no one expected it, we forced Republicans to make tough choices. We shaped the battlefield—and that matters. Because every close race changes the map for the next one.

I’m deeply grateful to everyone who made this campaign possible—from friends, interns, and operatives, to the Missouri Democratic Party and former colleagues who lent their support. And most of all, thank you to Jim Scaggs for having the courage to step up and run. It was an honor to be part of that fight.

We didn’t win. But we made it count. And sometimes, that’s how winning starts.